Defense Attorneys Need Not Fear the Reptile Strategy

The Reptile Strategy has garnered quite a bit of attention in recent years. And, perhaps, for good reason. However, if we play our cards right, we should be able to unveil it for what it is: highly manipulative. And once jurors become aware that they’re being manipulated, the strategy tends to backfire. In other words, the plaintiffs end up on the losing end of their own strategy.

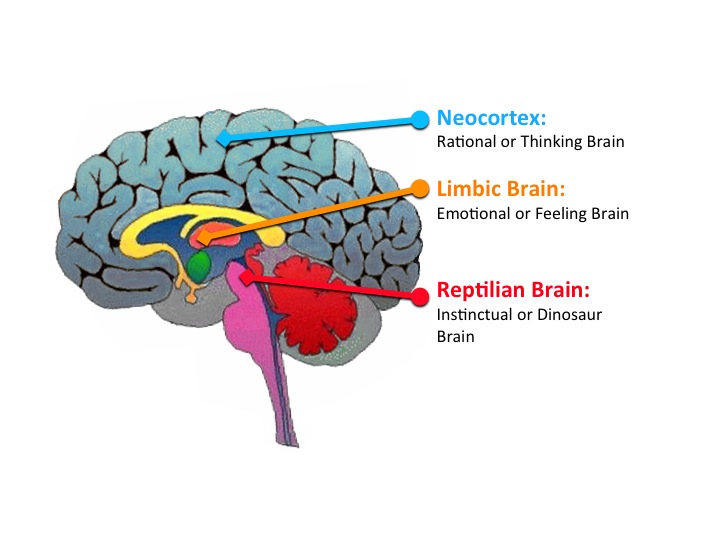

In effect, the Reptile strategy relies on the assumption that upon hearing about an injury or accident that our minds are hardwired not only to relate to the injured party, but to actually sense the danger for ourselves. The theory then follows that if we’re feeling threatened, we’ll move to protect ourselves, and in trial, the plaintiff as well. It’s an attempt to play on the emotions of others. But rather than garnering sympathy for the plaintiff, jurors are encouraged to feel anger for the defense.

In terms of damages, there’s no question that the attitude of “Let’s stick it to the defense!” is generally more lucrative than asking “What’s the plaintiff actually entitled to?” However, no one likes to be manipulated. And as soon as they discover that they’re being unscrupulously influenced, they tend to be offended.

According to Don Keenan, author of the “Reptile Theory”, the strategy only works if the injured party wasn’t specifically targeted. The reason is because in order to trigger the reptilian part of our brain we have to feel as if it could have happened to us. Individuals who are targeted are more difficult to relate to.

Nevertheless, although jurors are biased, generally speaking, they feel the weight of the responsibility to which they’ve been entrusted. Jurors want to get the verdict right. And they recognize that getting it right requires that they do their level best to set aside their pre-conceived notions and consider, aside from the emotion of the case, the actual evidence. Human nature may initially be inclined to respond to tragedy impulsively and emotionally, particularly when little is at stake, but let’s not make the mistake in thinking that jurors are so emotionally invested that their ability to evaluate the evidence objectively can be overwhelmed to the point of making obsolete other parts of the human brain; namely, the neocortex.

Therefore, to defend against the Reptile Strategy, defense attorneys should first expose it for what it is. Thereafter, they should trigger their own emotional response within jurors so as to, at the very least, counteract the effectiveness of the plaintiff’s emotional appeal, while simultaneously mounting an intellectually superior argument that is supported by the evidence and the rule of law.

CALL NOW : (619) 430-5879

CALL NOW : (619) 430-5879